Why Every Professional Cross-Trains

By Kyle Ligon - MovementLink Head Coach

How is it possible that time spent following just 1 workout program can generate results in all fitness areas that are close to each of the area specific programs?

Yoga, endurance, HIIT, weightlifting, powerlifting, bodybuilding, etc. each prioritize just one of these areas. This is absolutely necessary if you are trying to be the best in the world in a specific area. But, if you’re like most people and your goals are more broad and involve actually living life outside of the gym, you’ll want to consider avoiding the time and effort inefficiencies that inevitably exist when participating in these single-modality programs. The more I dug into learning from other programs the more I started to realize that the way amateurs follow programs looks nothing like the way professionals workout…not in amount, but style.

Creating an exercise habit may be the single most impactful thing you can do to benefit your life. But, unfortunately, quantity of effort is not the only determinator of the results you’ll get. Not only does sleep, nutrition, and non-exercise activity each play a vital role, but all exercise is not created equal and as you spend more and more time within an area of fitness, the diminishing returns for additional effort in that area skyrocket. The tendency is for people to get too focused on one or two narrow areas of training that resemble the athletic result they are after. For example, people who choose to focus on improving their running will only run. Typically, within that, their running workouts will also only be similar to the specific event they are interested in. Unfortunately, this unknowingly generates huge opportunity costs and wasted effort. Ironically, by doing less training that resembles the specific event and instead more strategically selected cross-training, these runners would produce much better running results in their chosen event.

For me, I had my cross-training epiphany after a couple years of lifting weights with the intent of growing muscle mixed with going for some runs each week for my “cardio”. I saw some results in those areas, but progress was very slow. Then, my childhood friend, Blake, who played collegiate baseball and was always super athletic and fit, came back into town and asked if I wanted to work out. I was excited to workout with him as I was always an athlete, but skinny and was proud that I had been working out. We did a high-intensity workout that coupled a few functional exercises with a barbell. I didn’t even know it was possible for a workout to destroy me as much as it did. It’s not like we did a huge thing, it was simple and only 20 minutes. I had been working out 5+ hours a week for a couple of years, and for what? I didn’t look all that fit and now definitely understood that I also wasn’t all that fit. I realized that if Blake would have picked workout that involved lifting weights with my standard 3 sets of 8-12 reps of a few exercises or if we would have gone for a slow run, I would have done just fine. But for anything else outside of that, my experience and fitness was extremely inadequate. I realized that almost every sport and all of life is outside of what my training transferred to. Instead of spending all of my time focused on just two styles of training, which left large gaps in my fitness, I exchanged that same amount of weekly exercise time into a strategically designed, holistic, functional fitness program. From that, I was not only able to achieve the original aesthetic goals I was after, finally, but with them came real fitness.

That started me on my functional fitness journey, and the more results I got the more I couldn’t understand why anyone serious about getting results would choose to train a single modality unless they were a professional who competed in a very specific sport. Ironically, as I have studied world-class athletes, coaches and programs across many disciplines, I realized that the single modality professionals don’t even train in a single modality, but everyone cross-trains in one form or fasion. The pareto principle can help show why.

The Pareto Principle and Opportunity Costs of Single-Modality Programs

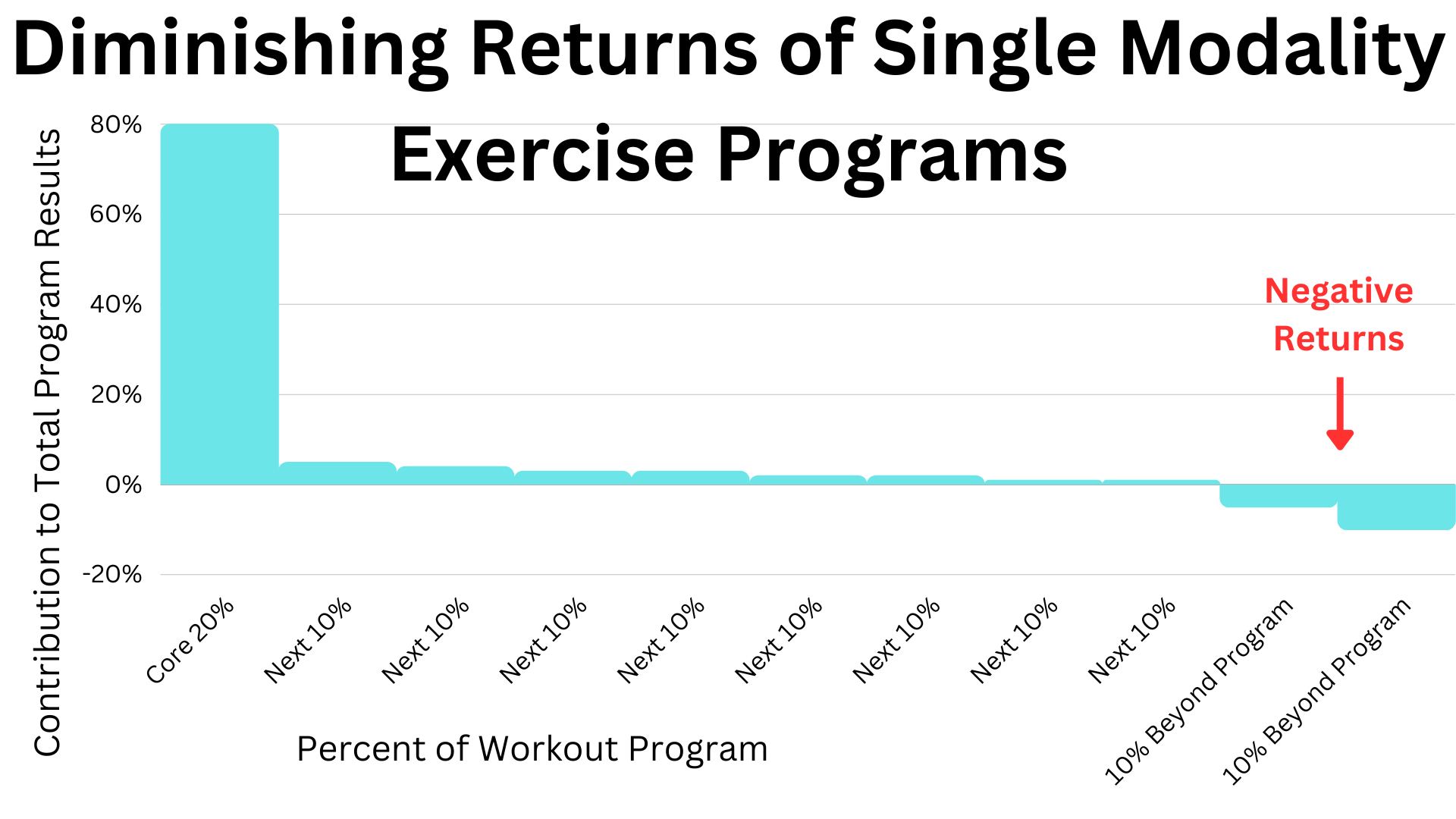

The Pareto Principle (The 80/20 Rule) states that, typically, 80% of outputs come from just 20% of the inputs. The remaining 20% of results come from having to put in an additional 80% of effort. This is obviously an overly general statement and cannot be applied precisely, but in the fitness world it does hold true that within a single modality exercise program, a smaller subset of core components of the program will produce significantly overweight results relative to the remaining majority of the program. In this article, I am going to use the percentages of the 80/20 rule from above not to claim these are the exact percentages, but instead to simplify how I refer to the minority core that produces the majority of the results and vice versa.

Any of the single modality programs above could work as a good example here, but let’s look at powerlifting. For context, a powerlifting program specifically targets performance in the sport of powerlifting - A competition where each competitor gets 3 attempts at a one rep max in back squat, 3 attempts at a max bench press, and 3 attempts at a max deadlift and the athlete’s best successful lift from each gets totaled up. Just a note that will be useful later: although “power” is in the name, powerlifting is much more of a strength sport than a power sport. A majority of the strength results of a powerlifting program come from a core amount of strength-specific sets using variations of their 3 core lifts. Out of the entirety of their workout program, most elite powerlifters only perform heavy strength sets on these exercises once a week. You read that correctly, the best in the world, even those who are taking performance enhancing drugs, typically only do strength work on each of these lifts once a week (Their core 20%). It’s not even whole workouts dedicated to strength, it’s strength sets that usually take up about half of a 1 hour workout that also includes sets of accessory work. The majority of their program (the remaining 80%) is spent doing exercises selected to enhance their strength work. In programs designed specifically to target just one fitness area, diminishing returns start to accumulate exponentially once you go past the core aspects of the programs.

I realized that with powerlifters able to squat and bench press over 1,000 pounds (sounds crazy, but that’s real), there was plenty of room to build tremendous strength without having to put 100% of my efforts into a strength program. The best marathon runners in the world average about a 4 minute and 30 second mile pace for the entirety of a marathon (absolutely insane). All areas of fitness have plenty of room to excel without the need a niche-specific program. When think about single modality programs, all I can see is enormous opportunity costs for every bit of extra energy being put into specific areas beyond that core 20%. Yes, it would be necessary if I was trying to be the best in the world, but not even remotely necessary to live the life I want to live. What if, after we have put in the core effort in one of these areas, instead of continuing to put efforts into the same things causing higher and higher diminishing returns, we shifted to the extremely high-return core of a different program?

As it turns out, the elite powerlifters and all the professional athletes I mentioned above have understood this for an extremely long time. It’s what they do. For strength development, the diminishing returns set in after those core strength sets, which only make up about 20% of their program. This is why they do exactly that amount. They don’t care about broad results, they only care about 1 rep max squat, bench, and deadlift. Surprisingly, if you want to be a poor performing powerlifter relative to other powerlifters, you would only strength train. If you wanted to be a poor performing runner relative to other runners, you would only run. If these athletes aren’t just training in their niche, what the heck are they doing with their time??? They are cross-training in very specific ways for their events.

I have realized that powerlifters cross-train for a very interesting purpose - to lay a foundation and improve their abilities while strength training. Instead of adding more strength sets beyond that core 20%, which would have high diminishing and eventually negative returns, powerlifters have learned that they can produce more strength results by instead developing the things that improve their strength training and give them more strength potential. I like to think of an elite powerlifting program as two separate programs done together: 1) A core strength program (~20% of their effort and produces about 80% of their results) and 2) Cross-training in a way that increases their performance in their core strength program (~80% of effort). The majority of their accessory work typically involves improving speed, power, and building muscle because those areas will help improve their ability to strength train. Speed and power helps them recruit muscle fibers faster. More muscle, give them more potential for strength. Some of the best in the world will even include some cardio, so that they are more capable of sustaining energy and intensity across their workout sessions. So, even though their only priority is maximal strength, powerlifters do not only work on maximal strength, but instead spend the majority of their time cross-training outside of the strength relm, but in a way that carries over to maximizing their strength results. It also turns out that the best marathoners in the world, also sprint and lift weights and sprinters perform a lot of weight training and long slow runs. It seems that the only people who do not cross-train are the amateurs who are adopting these single modality programs.

The Compounding Benefits of Cross-Training

Let’s look at one of many examples of a specific stimuli’s ability to compound benefits - What is called Lactate Zone 2 Training targets exercising at a specific, low-intensity effort level in which the lactate produced as a byproduct of muscle contractions is sustainable over long periods of time. At this low intensity, lactate is produced at or below the amount that can be removed from the blood as it’s recycled back to produce more energy. Supring to me, lactate is actually a preferred fuel of many cells in our body and is used as a fuel in exercise. Training in Lactate Zone 2 improves our mitochondrial ability to pull lactate out of the blood and use it for fuel. This is extremely beneficial for Endurance/Stamina, but the benefits don’t stop there.

Now, let’s say we are doing a high-intensity workout which will produce tons of lactate as a byproduct. If we have been participating in Lactate Zone 2 training, because we have become better at pulling lactate out of the blood and recycling it back into usable energy, we are able to sustain higher intensities for longer, making each single training session potentially that much more impactful. If we structure workouts and choose reps and exercises in strategic ways, these high-intensity workouts can be designed to have incredible carry-over back into endurance/stamina further boosting it while simultaneously carrying-over into boosting our strength/muscle and speed/power training. So, when we focus on the core 20% of training programs, those efforts do not exclusively produce the 80% of potential results within that area, but spills over and pushes the other areas past their 80%. When strategically organized, this can result in an extremely time- and effort- efficient style of exercising.

Time Efficiency

In addition to the time efficiency from compounding results, we can intentionally substitute parts of programs with methods from other areas. One example would be, instead of just warming up and cooling down on an exercise bike, we are highly purposeful with our time. We warm-up with the goals of doing functional, yoga-ish-looking exercises to progress our mobility as we simultaneously use those exercises to warm up and prepare for the specific demands of our upcoming workout. Our cool-downs also involve mobility exercises taking advantage of the similar breathing patterns that also benefit shifting us out of fight or flight mode from the workout and into recovery mode. The 10-20 minutes we would already need to spend warming up and cooling down serve a dual purpose of mobility and balance work. With this strategy, we accumulate 1-2 hours of mobility work each week, with no additional time added to our workout program. Not only that, but by basing our exercise and technique selection on functional movement patterns using full ranges-of-motion and always using our technique as our intensity-limiter, the core parts of our workouts continue to build our movement quality and mobility even further. This adds even more to that 1-2 hours of weekly exposure with no additional specific time spent.

The MovementLink Method strategically focuses on the core drivers of results in:

Mobility/Balance,

Speed/Power,

Strength/Muscle,

High-Intensity/Lactate Thresholds, and

Endurance/Stamina

and uses the carry-over benefits from each of these areas to further boost the specific training in each area creating a machine with compounding results.

While others cross-train for specific events, the MovementLink Method is a basket of exercise methods and lifestyle habits strategically selected and organized for anyone, regardless of age, gender, or fitness level, to, across our lifespan, directly target:

functional performance,

body composition,

joint and tissue health, and

overall health, wellness, and longevity.